Tuesday, December 12, 2006

UEPS rises! And other news...

Sunday, December 10, 2006

My Experiment in LEAPs

stock, I recorded the close price, as well as the close price of Jan. '07, '08 and '09 LEAPs with a strike price just below the close price of the security. Now, 4 months later, using the close as of December 8, I have determined the change in security and derivative values. LEAP values that expire in Jan. '08 and '09 changed in close accordance with stock price. (Click on the figure, and all figures, to expand them.) As the Jan. '07 expiry date approached, the LEAPs changed in price, in many cases dramatically. Of the 32 stocks that had options expiring in Jan. '07, the mean ± SD was 0.51 ± 1.05. This is a huge gain in that period of time, but much greater variability. The median change in value was 12%.

stock, I recorded the close price, as well as the close price of Jan. '07, '08 and '09 LEAPs with a strike price just below the close price of the security. Now, 4 months later, using the close as of December 8, I have determined the change in security and derivative values. LEAP values that expire in Jan. '08 and '09 changed in close accordance with stock price. (Click on the figure, and all figures, to expand them.) As the Jan. '07 expiry date approached, the LEAPs changed in price, in many cases dramatically. Of the 32 stocks that had options expiring in Jan. '07, the mean ± SD was 0.51 ± 1.05. This is a huge gain in that period of time, but much greater variability. The median change in value was 12%. by more than 10%? Figure 2 shows the distribution of LEAP by amount gained, as well as the gain for each category of LEAP. I think it is valid to then calculate an expected return: multiply the fraction in each category by the return of the category for an expected return in each category. By summing the expected returns of each category, you get the overall expected return, which is 17%.

by more than 10%? Figure 2 shows the distribution of LEAP by amount gained, as well as the gain for each category of LEAP. I think it is valid to then calculate an expected return: multiply the fraction in each category by the return of the category for an expected return in each category. By summing the expected returns of each category, you get the overall expected return, which is 17%. of the 50 portfolios resulted in a loss, averaging -11% ± 6.5%. By comparison, 11 of the 50 porfolios ended up more than doubling, with average returns of 115% ± 17%.

of the 50 portfolios resulted in a loss, averaging -11% ± 6.5%. By comparison, 11 of the 50 porfolios ended up more than doubling, with average returns of 115% ± 17%. have a better idea whether using LEAPs of MFI stocks improve returns. But, this data suggests that there may be an advantage to buying LEAPs of MFI stocks as compared to the stocks themselves.

have a better idea whether using LEAPs of MFI stocks improve returns. But, this data suggests that there may be an advantage to buying LEAPs of MFI stocks as compared to the stocks themselves.Friday, December 08, 2006

December buys, part I

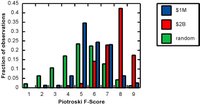

sort of short cut to #2, but only partly. So, in keeping with my previous analysis of MFI stocks, here's an analysis of the top 100 stocks with a market cap of at least $1M. (Actually, because of errors acquiring the F-Scores of a nuber of stocks, the actual sample size was 77.) It's a skewed distribution, weighted towards stocks with 'good' company characteristics, as defined by the F-Score. If you compare this distribution to that of my last analysis, there is a remarkable similarity (comparing to the distribution of companies with a market cap of at least $1M). Also, companies with higher F-Scores had larger market caps.

sort of short cut to #2, but only partly. So, in keeping with my previous analysis of MFI stocks, here's an analysis of the top 100 stocks with a market cap of at least $1M. (Actually, because of errors acquiring the F-Scores of a nuber of stocks, the actual sample size was 77.) It's a skewed distribution, weighted towards stocks with 'good' company characteristics, as defined by the F-Score. If you compare this distribution to that of my last analysis, there is a remarkable similarity (comparing to the distribution of companies with a market cap of at least $1M). Also, companies with higher F-Scores had larger market caps.WIld ride

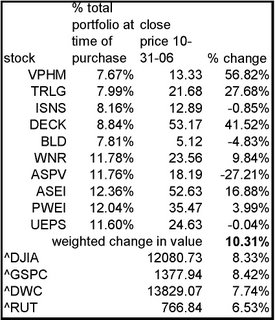

have been last month, but something kept me from it then. So today I bought my next round of MFI picks. Probably Monday will be my next round of Motley Fool picks. Before discussing what's new, here's a rundown of my portfolios to date.

have been last month, but something kept me from it then. So today I bought my next round of MFI picks. Probably Monday will be my next round of Motley Fool picks. Before discussing what's new, here's a rundown of my portfolios to date. consistent: only 2 of 10 are down, and one of those is OYO the yo-yo. The rest are all up to various extents - it's still a large range, but even the least of them is significant - NATH at 8%. The IRR of my HG portfolio is 62.6%

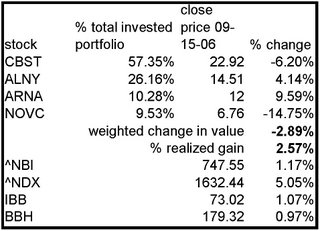

consistent: only 2 of 10 are down, and one of those is OYO the yo-yo. The rest are all up to various extents - it's still a large range, but even the least of them is significant - NATH at 8%. The IRR of my HG portfolio is 62.6% they thought they could bring the drug to that market, but the royalties will be alright. Both ARNA and ALNY have risen - ARNA dropped back down, but ALNY is just going higher and higher. What's interesting about the ALNY and ARNA stories is what's similar about them: they both announced that they'd sell shares. Why? The officers must believe that the shares are overvalued. The market ignored the ALNY announcement, but ARNA plummeted (still up overall, but down dramatically from their high). Now ARNA announced the sell price, and for some reason, the stock went to well above that price. Strange - I would have thought that would have set the price, rather than selling the bottom for the price. Anyway, the fact of the companies selling shares has made me wonder whether to sell as well. Or at least to take some off the table. ALNY especially has just kicked butt, mainly, I thought, because of the RNAI purchase and speculation that ALNY is also a buyout target. Not sure what I'll do for now.

they thought they could bring the drug to that market, but the royalties will be alright. Both ARNA and ALNY have risen - ARNA dropped back down, but ALNY is just going higher and higher. What's interesting about the ALNY and ARNA stories is what's similar about them: they both announced that they'd sell shares. Why? The officers must believe that the shares are overvalued. The market ignored the ALNY announcement, but ARNA plummeted (still up overall, but down dramatically from their high). Now ARNA announced the sell price, and for some reason, the stock went to well above that price. Strange - I would have thought that would have set the price, rather than selling the bottom for the price. Anyway, the fact of the companies selling shares has made me wonder whether to sell as well. Or at least to take some off the table. ALNY especially has just kicked butt, mainly, I thought, because of the RNAI purchase and speculation that ALNY is also a buyout target. Not sure what I'll do for now.Thursday, November 30, 2006

Great returns so far - but so what?

Sunday, November 26, 2006

UEPS in the Mayo Clinic

1. Can the company raise prices?

The answer is no. The product is for people without access to banks, or people for whom bank fees are prohibitive. These are not people who can afford to pay more. The UEPS model requires more people to be part of their network, not to charge their network high fees. Having said that, though, they are positioned to find new applications for their smartcard products - both geographically (old applications in new countries) and systematically (new applications in established countries).

2. Can the company sell more?

Definitely. Their technology has been broadly adopted in South Africa, they currently operate in Namibia, Botswana and Nigeria, and are exploring opportunities in nearby African countries, as well as a number of South American and South Asian countries. Third parties are operating their technology in Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Ghana, Rwanda, Burundi and Latvia. I would prefer that they were operating their own technology - to me this means that perhaps they couldn't keep make the most of their technology, and so resorted to licensing it out. But it's a start. In addition, they mainly operate by distribution of social welfare and payroll distribution; but they've identified additional mechanisms for adoption, including medical welfare distribution.

3. Can they increase profits on existing sales?

Not sure. Probably not, at least not any time soon. They need to expand as much as possible. Once much better established, they could probably spend less on network expansion, increasing the number of point of sales card readers, possibly once better established they can rely on government contracts to a greater extent than they do now. But for now, they need to reinvest the money they make into expansion. Revenue has gone up, but cost of goods sold has remained constant for 2005 and 2006.

4. Can the company control expenses? What is the outlook for SG&A?

SG&A went up $6M in 2005, and $3M in 2006. I showed earlier that SG&A is declining as a percentage of gross revenue, and this seems to indicate that the company is indeed controlling expenses.

5. If the company raises sales, how much goes to the bottom line?

Comparing 2006 and 2005 as an example, revenues went up a ton, cost of goods sold was constant, SG&A went up just a bit. This seems to be asking about the net profit margin, and I showed that this is increasing yearly. So historically, they've been successful with this - the question is whether they'll continue to do so, but there's no reason to think that they will not.

6. Can the company be as profitable as it used to be, or at least as profitable as its competitors?

The company is increasing profitability year-over-year. I'll compare it to competitors shortly.

7. Does the company have one-time expenses that won't need to be paid in the future?

Saturday, November 25, 2006

Back to the financial experiment...

Saturday, November 18, 2006

Part II

Step 1: Revenue is listed for 2004 through 2006, and increased each year. 11.2% in 2006, and 34.5% in 2005. It is not particularly encouraging that revenue growth declined. Have they made the largest gains in market penetration (really, creation, given what they do)? This is probably why they are looking to diversify into new countries.

Step 2: The cost of goods sold increased by ~20% in 2005, but remained unchanged in 2006. As they grow as a company, does this indicate that they are streamlining production? Have they found cheaper labor or materials or products? It is perhaps a network effect: once the network is in place, there are perhaps only smaller charges to maintain it.

Step 3: Gross profit is revenue minus the cost of goods sold. 2006 - $146M; 2005 - $126M; 2004 - $92M. So, gross profit is increasing yearly. Browne says that he likes for this number to be stable, but clearly it isn’t. I suspect that is typically for a more mature company, but who knows?

Step 4: Determine operating profit by subtracting SG&A from gross profit. 2006 - $97M; 2005 - $80M; 2004 - $52M. As a % of gross revenue: 2006 – 32%; 2005 – 37%; 2004 – 43%. So with this number coming down percentagewise, this is probably a good thing. Browne says that this is the earnings before interest and taxes, EBIT, that is so important for the MFI, actually, and, Browne continues, this is the number that is used to value the company, including people looking to acquire it. The UEPS income statement includes depreciation and amortization in calculating the operating profit, as well as reorganization charges in 2004 and costs associated with the IPO and continued Nasdaq listing. The Nasdaq charge is probably more or less recurring, but it seems to me that the IPO cost and the reorganization charges should probably be ignored for calculating EBIT. And when depreciation and amortization are included, it becomes EBITDA. I’ve heard elsewhere that EBIT is more important than EBITDA.

Step 5: Calculate EPS. It took a little searching in the annual report to find a clear statement of the number of shares outstanding, but finally, the “Total weighted average number of outstanding shares used to calculate earnings per share – diluted” is 57.3M. So, using EBIT as earnings, EPS is 97 / 57.3 = $1.69. Using nondiluted shares EPS = $1.72, not a big difference at all. And looking at the other 2 years: 2005 – dil, $1.43, nondil, $1.46; 2004 – dil, $1.50, nondil, $1.56. A large number of shares were issued in 2005, increasing the number of shares 60%. So that explains the drop in EPS in 2005, but now in 2006, the EPS has more than made up for the dilution of ownership.

Step 6: Calculate the ROC: Divide the earnings of any year by the beginning year’s capital (ie, the end of the previous year), which is the shareholder’s equity and total liabilities. In this case, then the EBIT for 2006 is $97M, while the capital is $182M. ROC is 53%. ROC is of course one of the two measures for identifying MFI stocks, and this is a pretty high number for ROC. I’m encouraged that I came up with a number that seems appropriate for a MFI stock.

Step 7: The net profit margin is the earnings divided by the total revenues, presumably using EBIT as earnings. 2006 – 49%; 2005 – 45%; 2004 – 40%. So profit margins are increasing, which means that reinvesting cash in the company is leveraging sales.

Coming up is taking the stock to the mayo clinic. This one has more to do with everything the company has to say about their business, and less to do with the balance sheet and the income statement. This part is harder, and I’ll wait a little for it.

One last thing: I bought UEPS at $24.64. With EPS of $1.69, this gives an earnings yield of 7%. This sounds low for a MFI stock. When I get back the Little Book That Beats the Market, I’ll have to double check how EY is calculated for MFI.

But overall – that wasn’t so hard. Really.

You've taken your first step into a larger world - Obi-Wan Kenobi

The most directly useful part of the book are three chapters that discuss how to value a company. Coincidentally, the same day that I finished the book, I received in the mail the year-end report for Net 1 UEPS, one of the stocks that I own in my MFI portfolio. I decided to evaluate UEPS using the steps outlined by Browne (he doesn’t actually list them as ‘steps’ – these are my arbitrary divisions of his commentary). Here goes.

Step 1: Current assets and current liabilities. The current assets are ~$240M, and the current liabilities are ~$40M, so the current ratio is 6. Browne says at least 2:1 – UEPS is doing well. The working capital is ~$200M; Browne says the more the better. The quick ratio is the (current assets – inventory) / current liabilities. Inventory is only ~$2M, so the quick ratio is only marginally different from the current ratio.

The 2005 current ratio was roughly 5, and the working capital was ~$115M. So 2006 seems an improvement over 2005.

Step 2: Long term assets and liabilities. Total LT assets are ~$29M; Browne says to subtract out intangibles and goodwill, so he would consider LT assets as ~$11M. The only long-term debt listed is deferred income taxes, at ~$18M. How does this compare to last year? In 2005, LT assets were ~$30M, or ~$9M excluding intangibles and goodwill. LT liabilities were ~$10M in 2005. So, LT assets (excluding intangibles) went up ~20%, while LT liabilities increased 80%. However, the long-term liabilities are small compared to cash on hand, never mind short-term assets. This seems healthy.

Step 3: Book value. Subtract all that the company owns from all that it owes: $209M. Browne suggests subtracting intangibles here as well, so the book value is $189M. The debt to equity ratio is ~0.3. This means that the company is funded primarily through investment. In 2005, this value was ~0.4, so this also seems to be improving. Browne says that even if this number is greater than 1 it’s not the end of the world, so the small improvement in debt to equity ratio seems not particularly important. What is important, I think, is that the value is significantly less than 1.

I’m going to skip step 5 for now: comparing the book value of UEPS to its competitors. This brings me to the end of the first chapter about evaluating a company, and it seems that the balance sheet shows that UEPS has a solid foundation.

Tuesday, October 31, 2006

Earnings Announcements, Update, and ASPV Thoughts

DECK kicked butt, reporting $0.83 per share, up from $0.63 compared to the same quarter last year. This blew away analyst estimates of $0.54, and the stock price jumped ~ 8%.

ISNS stunk it up. BLD was flat with last year. ALDN beat estimates by $0.03, and stayed pretty much flat, also.

SCSS came ahead of analysts estimates, but said that sales slowed towards the end of the quarter and so the stock price slid 17%.

Income nearly tripled for ATHR with 74% increased sales.

ARNA lost $20M on R&D, and stayed high, still for no real reason. It seems to have settled at ~$15, and as long as it stays around here, I'm happy.

Merck bought Sirna at a huge 100% premium. This sent ALNY up ~20%, as pretty much the only independant microRNA company left. Pretty sweet.

Finally, I want to talk about ASPV. This one is a whopper. First, it announced that it would miss analyst estimates for the quarter. It reiterated that for the year it would make 163% of last year's earnings. But still, it dropped 10%. I thought that was way less bad than the market thought. And then they announced that their drug didn't pass phase III trials for another indication, and the stock dropped another 11%. At this new price, the PE is ~6.5 TTM, with a forward PE of ~5.3. All of this together got me thinking. The CellCept patent runs out in 2009. So shareholders can count on about 2-3 more years of great earnings, and then the well dries up. Unless, that is, the company finds either another drug or another indication for their drug. It's a bit of a desperation situation. Another way of looking at this is: the PE is the number of years it takes for the current earnings per share to pay back the investment. From this perspective, investors at this point are betting 2.3 years worth of earnings that the company will find some way

to remain profitable beyond the patent protection of CellCept. If they do find some way to remain profitable, the PE should shoot up to some amount beyond the patent protection or other limit of the new drug in question. The years worth of betting on management amount to 43% of the PE. Cash per share, after subtracting the miniscule amount of debt, is $5.50. So of the remaining cost of the share, is 43%, or ~$5.60, represents the bet that management will find a new drug, or a new indication for their drug, within the next few years.

to remain profitable beyond the patent protection of CellCept. If they do find some way to remain profitable, the PE should shoot up to some amount beyond the patent protection or other limit of the new drug in question. The years worth of betting on management amount to 43% of the PE. Cash per share, after subtracting the miniscule amount of debt, is $5.50. So of the remaining cost of the share, is 43%, or ~$5.60, represents the bet that management will find a new drug, or a new indication for their drug, within the next few years.Monday, October 23, 2006

Cubist's Earnings and the Market's Expectations

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

Efficient market vs. semi-efficient market vs. inefficent market

Sunday, September 17, 2006

New HG buys and update

But still, the reasons for these purchases might be a little weak if I didn't have some trust in HG picks. Here they are: OYOG is only slightly above the recommended buy price from a few months ago. SCSS and MIDD are two of the three strongest recommendations that HG'ers have made. They keep on re-recommending them, and also they are on the HG list of best places for new money. This isn't what convinced me, though. It was that they have high Piotroski F-Scores. Finally, NATH is a Tiny Gem (below the official HG radar, like ALDN), but it is on the current list of MFI picks and has 16% ownership by insiders.

But still, the reasons for these purchases might be a little weak if I didn't have some trust in HG picks. Here they are: OYOG is only slightly above the recommended buy price from a few months ago. SCSS and MIDD are two of the three strongest recommendations that HG'ers have made. They keep on re-recommending them, and also they are on the HG list of best places for new money. This isn't what convinced me, though. It was that they have high Piotroski F-Scores. Finally, NATH is a Tiny Gem (below the official HG radar, like ALDN), but it is on the current list of MFI picks and has 16% ownership by insiders. Finally, ISNS is recovering from its slump: from -12%, it is now only -4%.

Finally, ISNS is recovering from its slump: from -12%, it is now only -4%.

My first experiment in finances

- I don't know how random the generator was: in a sample of 180-odd stocks, there were five repeats. This seems high considering the sample size relative to the total universe of stocks.

- Piotroski F-Scores were found using an Excel Add-In; in some cases it returned an error. So the actual sample sizes were: $1M - 78; $2B - 92; Random - 94.

- The $1M portfolio simply includes the top 100 stocks in the current MFI screen, with the range of market caps from $15M (ANTP) to $14B (NUE), with a median value of $439M.

- The $2B porfolio has a range of market caps from $2.013B (HNI) to $384B (XOM - Exxon Mobil), with a median value of $5.59B.

- The randomly-generated portfolio had a range of market caps from $7.4M (VERT) to $60.8B (QCOM - Qualcomm), with a median of $187M.

- What is the statistical significance of this experiment? In order to be truly confident in these results, in other words, to be sure that the different distributions are not soley due to chance, this experiment should repeated some large number of times, say 1000. I think that a t-test might be valid, but I also think that there might be a problem because the MFI portfolios have a skewed (rather than perfectly normal) distribution. In case they are valid, I'll just mention that the P-vaues for the $1M and $2B portfolios, as compared to the random portfolio, are 0.0005 and 5e-12, respectively.

Click on the figure to expand it. The group of random stocks is pretty  much normally distributed, while the $1M and $2B MFI stocks are right shifted. There were no stocks in the $1M portfolio with a F-Score less than 2, and none in the $2B portfolio with a F-Score less than 3. The $2B portfolio is skewed towards higher F-Scores.

much normally distributed, while the $1M and $2B MFI stocks are right shifted. There were no stocks in the $1M portfolio with a F-Score less than 2, and none in the $2B portfolio with a F-Score less than 3. The $2B portfolio is skewed towards higher F-Scores.

It makes sense that no MFI stock has a 0 or a 1 F-Score: MFI stocks have a high earnings yield and return on invested capital, which should be closely related to accrual (or maybe CFO) and ROA. But, it is surprising that the large cap portfolio is the one that is further right-shifted than the total MFI portfolio. Both Piotroski and Greenblatt concluded from their analyses that small cap stocks are better performers when selected by their respective methods. So why does a broader portfolio score worse than a focused, high market cap portfolio? What's the difference between Piotroski and MFI? I think that the difference is important, actually. MFI uses two characteristics, but the ranking system lets the screen scale the potential performance of the stocks. In other words, the one stock with a F-Score of 2 probably scored really highly on those two characteristics - but the F-Score fails to take that into account because it is based on binary analysis for all of its characteristics. Is there some way to combine the two approaches? Sure. For every stock, rank it for each Piotroski characteristic. Combine the rankings for an ordered list, like in MFI.

Is this necessary? Maybe not. Greenblatt argues that EY and ROIC are the major determinants of performance. And I think that MFI and Piotroski analyses are supposed to give comparable returns - possibly even MFI is superior, I think. So is Piotroski diluting the effects of the MFI characteristics by including the 7 other characteristics? What are the relative effects of each Piotroski characteristic? Rerun the Piotroski analysis 9 times, but for each rerun, make one of the characteristics worth 3 instead of 1. If this results in superior outcomes in terms of portfolio change, then you've identified a more important characteristic. This can be confirmed by systematically dropping one characteristic from the Piotroski F-Score, and looking for an increased drop in portfolio returns relative to dropping any of the other characteristics.

Finally, how does this affect my stock buying strategy? I'm not sure so far, because I'm not sure that I want to mess with something that's working. My current MFI strategy is:

- Pick stocks from the top-100 stocks with a minimum market cap of $1M.

- Buy 5 stocks every 2 months.

- Prefer stocks with recent insider purchases.

- Prefer stocks that have high insider ownership.

I'm considering adding the following rules:

- Only buy stocks with a high Piotroski F-Score.

- Only buy stocks with low or no analyst coverage. I rather like this one, as it typically means that Mr. Market has a worse idea of how to value any given stock.

I suspect that few stocks will meet all of these rules. This might involve checking the MFI top 100 more often than every 2 months and buying whenever I find a stock that does meet all of these criteria.

Sunday, September 10, 2006

A homegrown screen?

1) Small cap (<$1.8B)

2) Highest 20% in the market for Earnings Yield

4) Top 40% in the market for each of Return on Equity, Return on Investments and Return on Asests

5) Lowest 20% Institutional Ownership

6) Highest 20% Net Insider Purchases

7) Covered by 4 or fewer analysts.

I came out with three companies. And the winners are...

Second Round of MFI

Thursday, August 31, 2006

A new portfolio

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

LPMA

Update

erday that were positive, and the market put it up over a buck in after hours trading. For me what this really means is that the company knows that it needs products to take over from vancocin, and this means that they're on their way. A pipeline can't hurt, that's for sure. TRLG announced that they're opening stores in Palm Beach, I think NYC, and now Latin America. There are rumors that they're shopping themselves out to be bought out. It seems that this is common for MFI stocks: there've been a couple, and IVII (not IIVI from my HG portfolio) just announced that they were being bought out at a 30% premium yesterday. DECK announced great earnings, and that shot them upwards. It's not as clear what's going wrong with the two that are down.

erday that were positive, and the market put it up over a buck in after hours trading. For me what this really means is that the company knows that it needs products to take over from vancocin, and this means that they're on their way. A pipeline can't hurt, that's for sure. TRLG announced that they're opening stores in Palm Beach, I think NYC, and now Latin America. There are rumors that they're shopping themselves out to be bought out. It seems that this is common for MFI stocks: there've been a couple, and IVII (not IIVI from my HG portfolio) just announced that they were being bought out at a 30% premium yesterday. DECK announced great earnings, and that shot them upwards. It's not as clear what's going wrong with the two that are down. by speculation and also by the institutional investors, which have now bought up 12.7% of the outstanding shares. I had thought that buying when I did was low enough, but maybe one or more mutual funds had to sell off as the price dropped. Who knows? I still think that the companies I have are great for long-term plays, but none are going to really quickly go up by some huge amount. I've invested more in this portfolio than I'd originally intended (a little too much enthusiasm, that I recognize as a beginner's mistake) so I may sell off some of this portfolio in an effort to balance the three portfolios.

by speculation and also by the institutional investors, which have now bought up 12.7% of the outstanding shares. I had thought that buying when I did was low enough, but maybe one or more mutual funds had to sell off as the price dropped. Who knows? I still think that the companies I have are great for long-term plays, but none are going to really quickly go up by some huge amount. I've invested more in this portfolio than I'd originally intended (a little too much enthusiasm, that I recognize as a beginner's mistake) so I may sell off some of this portfolio in an effort to balance the three portfolios. ebannon (it's an Israeli company). CTRP went up, down and is now up again. Funny, I would have thought that it would have been the fastest riser, but of course this is way too short to say anything meaningful about that.

ebannon (it's an Israeli company). CTRP went up, down and is now up again. Funny, I would have thought that it would have been the fastest riser, but of course this is way too short to say anything meaningful about that.Thursday, August 24, 2006

Was it a mistake?

Exciting week

Monday, August 07, 2006

Risk and leverage

Alberto-Culver

And, to keep my eyes open for more spin-offs.

Scorecard

activity. In separate panels are my own biotech picks, my MFI picks and my Hidden Gems picks, and relevant indexes for comparison. What are the highlights? DECK has been nice to watch. They just announced earnings that were way ahead of guidance, but not that much improved relative to last year. Nevertheless, I guess the street liked what they heard. Everyone seems to be talking about Simple, UGG and the return of Teva sandles. Which is great for DECK.

activity. In separate panels are my own biotech picks, my MFI picks and my Hidden Gems picks, and relevant indexes for comparison. What are the highlights? DECK has been nice to watch. They just announced earnings that were way ahead of guidance, but not that much improved relative to last year. Nevertheless, I guess the street liked what they heard. Everyone seems to be talking about Simple, UGG and the return of Teva sandles. Which is great for DECK. about these stocks. Let the companies have the chance to report on earnings for a few more quarters (CBST) or hopefully some other surprises (MEDX and maybe ALNY in particular). These picks are speculative, based on the probability of the technology paying off. And are definitely buy and hold plays. NBIX spectacularly showed how that could end up - on the downside. More in later posts.

about these stocks. Let the companies have the chance to report on earnings for a few more quarters (CBST) or hopefully some other surprises (MEDX and maybe ALNY in particular). These picks are speculative, based on the probability of the technology paying off. And are definitely buy and hold plays. NBIX spectacularly showed how that could end up - on the downside. More in later posts.

Cubist

Saturday, August 05, 2006

Reading List

Get a Financial Life - Beth Kobliner

9 Steps to Financial Freedom - Suze Orman

The Little Book That Beats the Market - Joel Greenblatt

You Can be a Stock Market Genius - Joel Greenblatt

One Up on Wall Street - Peter Lynch

Beating the Street - Peter Lynch

This is on my nightstand:

The Intelligent Investor - Benjamin Graham

I discommend these:

The entire 'Rich Dad, Poor Dad' series.

Lesson #1

Savings

Just to clarify about savings... I didn't mean that saving is a bad idea. The point is that I've pretty much got that part down. Given the salary I make, I think it's fair to say that I save a pretty good amount. So the question won't be about whether I save enough - it will be about whether the returns I get are sufficient to turn my savings into 'enough.'

The Starting Line and the Strategy

Primer

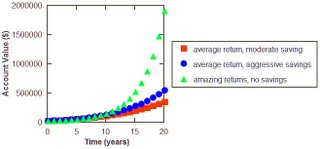

amazing it really can be. It seems pretty common to assume a $10K starting investment, so I've done that here. "Average returns" is the (more or less) 11% historical return of the market. "Modest savings" is $4K per year, the amount to max out a Roth IRA. The maximum investment in a Roth is bound to go up, but I left it at $4K for the entire time of the series. "Aggressive savings" assumes that the amount saved will go up every few years - to $6K in 3 years, to $8K in 6 years, and so on. "Amazing returns" is the 30% suggested by MFI.

amazing it really can be. It seems pretty common to assume a $10K starting investment, so I've done that here. "Average returns" is the (more or less) 11% historical return of the market. "Modest savings" is $4K per year, the amount to max out a Roth IRA. The maximum investment in a Roth is bound to go up, but I left it at $4K for the entire time of the series. "Aggressive savings" assumes that the amount saved will go up every few years - to $6K in 3 years, to $8K in 6 years, and so on. "Amazing returns" is the 30% suggested by MFI. st few years, saving helps a lot. But within ten years, MFI beats the more moderate returns. Here's a zoom on the first twelve years. (I added in a data set for amazing returns with moderate saving, because that is realistic - and in this case, average returns, even with aggressive savings, never wins.)

st few years, saving helps a lot. But within ten years, MFI beats the more moderate returns. Here's a zoom on the first twelve years. (I added in a data set for amazing returns with moderate saving, because that is realistic - and in this case, average returns, even with aggressive savings, never wins.) This was the data that made something very clear to me: The classic Suze Orman example of how to save an extra few bucks for retirement is to not drink coffee every day. That $4 at Starbucks really adds up! Well, I don't even drink coffee. As far as I'm concerned, I've saved a huge amount given that I've only ever been a graduate student and a post-doc. And if I listened to Suze, I'd never save enough to have even $1M at this rate - and my expenses are only going to rise.

This was the data that made something very clear to me: The classic Suze Orman example of how to save an extra few bucks for retirement is to not drink coffee every day. That $4 at Starbucks really adds up! Well, I don't even drink coffee. As far as I'm concerned, I've saved a huge amount given that I've only ever been a graduate student and a post-doc. And if I listened to Suze, I'd never save enough to have even $1M at this rate - and my expenses are only going to rise.